The Clean Energy Future Blog

The Value of Public Investment in Green Banks

By Coalition for Green Capital

The track record shows that a Green Bank can drive more investment, more clean energy, and more CO2 reduction per dollar of public cost than current programs.

The longest running Green Banks in the U.S. have now been operating for over five years. Green Banks have driven over $2 billion of clean energy investment in the U.S., and $26 billion globally as of 2016. Collectively those Green Banks have driven more than $3 of private investment per each $1 of public investment used.

But, now that the track record exists, it is important to ask if Green Banks really are accomplishing good outcomes and getting value for public money. Should policymakers invest public money in Green Banks?

A simple way to answer that question is to compare Green Bank outcomes to those of what can be considered the “benchmark” policy for clean energy investment across the country – utility efficiency incentive programs. Utilities use ratepayer and public funds across the country to offer nearly $8 billion per year through incentive programs to spur demand for efficiency and “procure least cost resources.” Regulators direct utilities to operate these programs to reduce overall energy demand and defer construction of new generation capacity.

Green Banks are intended to achieve similar (though slightly different) energy, economic and environmental outcomes. They seek to maximize the deployment of affordable clean energy (renewable and efficiency) and maximize total investment (both public and private). Green Banks use a range of financing techniques and program design structures to draw in capital and make markets grow.

Incentives and Green Banks are complementary and often are used together in the same project. Cash grants and rebates can entice demand, and financing can enable would-be adopters to buy clean energy technology with no upfront cost. It is not an either/or. Since incentive programs exist everywhere, though, they provide a useful basis of comparison of what energy, economic and environmental outcomes can be achieved with public investment.

The best point of comparison is Connecticut, whose Green Bank has operated for over five years. And because the Green Bank was capitalized by re-directing a small portion of the funds previously used for incentives, the state provides a test case for Green Bank evaluation.

The case for Green Banks is clear. On many energy, economic and environmental metrics, the Connecticut Green Bank has superior outcomes.

- In the three years from 2014 to 2016, the CT Green Bank has saved or generated 50% more clean energy per dollar of public cost than the incentive programs. Even if the Green Bank lost every dollar it loaned (turning that loan into a cost), the Green Bank would still perform on par with incentive programs.

- And the Green Bank has reduced 50% more CO2 emissions per dollar of public cost than incentives. Again, even if the Green Bank lost every dollar it loaned, the Green Bank would still perform as well as the incentive programs.

- Green Banks leverage more private clean energy investment per dollar of public investment than the incentive programs. Over the last three years, the Green Bank leveraged $4.65 of private investment per dollar of public investment, compared to only 90 cents of private investment for incentive programs.

- The Green Bank also puts more of its money into project investment rather than operating expenses. Over the last three years, only 25% of the funds used by the Green Bank went to operating expenses. For the utility incentives, this figure is 34%.

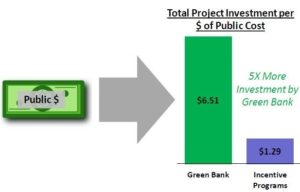

- The higher leverage and operating efficiency means that the Green Bank drives 5x more clean energy investment per dollar of public cost than the incentive programs.

- In addition to realizing greater energy, environmental and investment outcomes, the Green Bank has actually paid dividends to the state. The Green Bank has paid $25.4 million to the state government to fill budget shortfalls. This is possible because the Green Bank preserves capital by offering financing. Incentive programs cannot make these kinds of direct cash dividends.

By these measures of capital efficiency and outcomes, Green Banks represent a strong and wise investment of public funds. And policymakers around the country can realize similar benefits by creating and funding their own Green Banks.

As stated before, Green Banks and incentives are complementary. There need not be a debate between financing versus subsidies (though some organizations continually want to force that debate). But a data-driven analysis shows us that Green Banks can clearly improve the energy, economic and environmental outcomes any state aims to achieve through public investment in clean energy deployment.

Click here for the details of the supporting analysis.

CGC Roundtable: Green Banks in Emerging Markets

By Coalition for Green Capital

The Coalition for Green Capital hosted a high-level roundtable on Green Banks in Emerging Markets on April 21, 2017 in Washington, DC. The event, organized alongside the IMF spring meetings, featured leading climate finance experts from government, private finance and the NGO community. The day was organized as a discussion, exploring how Green Banks (through either purpose-built entities or adaptations of existing institutions) might facilitate an increased flow of investment into low-carbon projects in developing economies at the scale required to achieve international climate goals. The session was engaged, wide-ranging and productive and was grounded in an understanding that business-as-usual will not get us to our goals. As estimated by the OECD, post-Paris commitments by Development Financial Institutions will result in an approximate increase of $46 billion annually (including public finance + private leverage) towards the annual low-carbon investment gap[1]. This only fills 6.1% of the IEA estimated $759 billion annual gap that exists between current investment levels and the “Meet NDC” scenario[2].

The discussion was also grounded in an understanding that getting private capital to move quickly and at scale will require market conditions that will support both competitive returns and provide affordable low-carbon for customers. To achieve these conditions of attractive returns and affordable energy, discussion focused on understanding the gaps and barriers that need to be bridged and how national Green Banks can play a useful role in the evolving climate finance architecture.

A key take away from the discussion was that Green Banks offer a flexible model for country-specific approaches. It was noted that form must follow local function, and the first step is to identify what local barriers exist. Taking the Green Bank concept forward, will require a shift from the general macro concept to identifying country-specific opportunities around priority markets, gaps and barriers. Participants acknowledged that powerful new approaches are needed that are focused, accelerated, dedicated, at scale and local.

It was also noted that the time is ripe for innovative thinking about local ownership of climate finance. Participants pointed out that investment decisions are inherently local, and there is growing demand for local solutions. Post-Paris, as countries around the world look to convert their NDCs into investment pipelines, Green Banks offer a useful mechanism to support local ownership and increasing investment in a way that allows for autonomy, flexibility and valuable political signaling.

Major themes of discussion centered on speed, scale, focus, retail and wholesale bridges, capacity (either new or adapted) and mainstreaming green investment. The discussion also focused on the need to address resilience and adaption as part of the climate finance approach in emerging markets.

Next steps coming out of the event are for CGC to incorporate the ideas and thinking that emerged from the scoping session into recommendations for the Hewlett Foundation on how to approach Green Bank creation (through new and/or existing institutions) in developing countries. CGC’s approach will focus on two broad levels. First, we will work to identify a small set of promising pilot countries or sub-national locations for potential Green Banks and build a phased implementation plan around these initial locations. Secondly, we will use these pilot projects to develop systematic approaches to institutional engagement of capital providers, investors and other major stakeholders in the clean energy finance architecture.

[1] OECD, “2020 Projections of Climate Finance Towards the USD 100 Billion Goal; Technical Note,” 2016.

[2] Clean energy includes renewable energy, energy efficiency, and other low-carbon technologies, such as nuclear and CCS. IEA, “World Energy Outlook – 2016,” OECD/IEA, 2016.

By Coalition for Green Capital

Reed Hundt, the CEO of Coalition for Green Capital, recently delivered a presentation for the International Monetary Fund on the potential for clean energy and 5G communications technology to drive global economic growth.

Reed discusses the clean energy investment opportunity presented by the annual global investment need of $200 billion over the next 25 years. The amount of total investment in energy doesn’t need to change—but the share of investment that goes to carbon vs clean must be reversed. This “big switch” is an opportunity that will drive global growth, and increase climate security.

The slides for Reed’s presentation are available here.

By Coalition for Green Capital

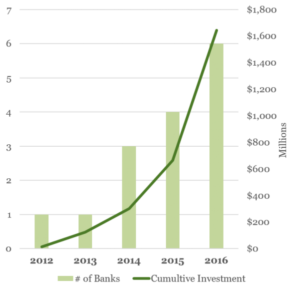

Since the first Green Banks in the US were founded, the number and investing pace of these institutions has ramped up.

Since the first Green Banks in the US were founded, the number and investing pace of these institutions has ramped up.

CGC reviewed annual reports and transactions at six US-based Green Banks from their inception through fiscal year 2016. At the end of 2016, the transactions these institutions participated in represented more than $1.6 billion of cumulative clean energy investment. Nearly $1 billion of that total came from private sources, demonstrating the continuing ability of Green Banks to leverage private dollars.

The investment pace is poised to accelerate in fiscal year 2017. Last month NY Green Bank announced the close of 13 transactions, totaling over $900 million. This set of transactions alone places total investment well over the $2 billion mark.

The six Green Banks reviewed were: the California Lending for Energy and Environmental Needs (CLEEN) Center, the Connecticut Green Bank, the Hawaii Green Energy Market Securitization (GEMS) Program, the Montgomery County Green Bank, the NY Green Bank, and the Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank.

By Coalition for Green Capital

In work related to COP 21 in Paris, the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) called for use of a systemic platform across the financial system to support creative collaboration to expand innovation in climate finance. This call for building a coalition across the financial system and coordinating efforts through a systemic platform is identified in CPI’s The Global Landscape of Climate Finance. The Coalition for Green Capital and the Natural Resources Defense Council, have partnered with a group of six Green Banks to create a new international Green Bank Network to help increase and accelerate investment in renewable energy and energy efficiency worldwide. This new platform is the kind of systemic collaboration that CPI has identified as a powerful driver for taking clean energy finance and investment to scale through sharing best practices and innovations and expanding the growing network of Green Banks across states and countries. This new initiative will be launched on Dec 7 at an OECD COP 21 session on “Green Investment Banks: Leveraging Innovative public finance to scale up low carbon investment.”

By Coalition for Green Capital

Two new reports from global leaders in climate finance identify the important role that public capital should play in scaling up private investment. Though neither explicitly names Green Banks, both effectively articulate the need for Green Bank-like solutions.

One report, from the Climate Policy Initiative, on key lessons in climate finance emphasizes the interaction of public and private finance:

National and international public finance play key roles building projects’ bankability by covering viability and knowledge gaps, driving huge increases in investment from the private sector.

Another report, authored by the International Finance Corporation, says there are $23 trillion in climate investment opportunities, and that public investment will play a crucial role in facilitating more private investment in that space:

Using public finance to scale up support for project preparation and development can play a critical role in encouraging investment. Furthermore, to attract private capital, investments must have adequate risk-adjusted returns and be of suitable size. This is particularly important in newer climate business areas where perceived risk is high, such as energy storage, or where aggregation models are unfamiliar in a developing-country context. Governments can increase their efforts to reduce risk (for example, by blending public and private finance), while also helping to aggregate smaller, de-risked assets, diversified across sectors and geographies, to attract institutional investors.

Both reports highlight the need for public dollars to prime the pump for private investment in clean energy. This exactly the role of Green Banks!

Green Banks have a proven history of doing exactly what these reports call for—deploying public capital to de-risk and increase private investment in clean energy projects. Examples of successful Green Banks include the Connecticut Green Bank, NY Green Bank, UK Green Investment Bank, Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank, and the Australian Clean Energy Finance Corporation—each Green Bank has used public dollars to increase private investment in clean energy. And by leveraging more private investment, Green Banks increase the impact of each public dollar devoted to deploying clean energy.

Green Banks are an important and effective tool in climate and energy finance. Global thought leaders clearly understand the value of the Green Bank approach. Now the institutional model needs to be spread around the world. This coming week, NRDC will hosting an event on Green Banks at COP22 in Morocco, and CGC will be speaking about Green Banks at an IDB-hosted conference in Lima on innovative finance.

Green Banks are an important and effective tool in climate and energy finance. Global thought leaders clearly understand the value of the Green Bank approach. Now the institutional model needs to be spread around the world. This coming week, NRDC will hosting an event on Green Banks at COP22 in Morocco, and CGC will be speaking about Green Banks at an IDB-hosted conference in Lima on innovative finance.

Follow

The Clean Energy Future Blog

for links, analysis, and commentary on the world of green banks and clean energy investment