The Clean Energy Future Blog

By Coalition for Green Capital

A National Infrastructure Bank, once called “the next best idea for the past 25 years,” looks like it may soon become a reality. Infrastructure has received considerable attention this election season, and Hillary Clinton has unveiled her plans for a $25 billion National Infrastructure Bank. The recently introduced Green Bank Act of 2016 has sparked interest in how a National Green Bank would fit with a National Infrastructure Bank. This post breaks down the similarities and differences between the two institutions.

Similarities

While the details of the latest version of the National Infrastructure Bank are still to be determined, it will likely share several similarities with the National Green Bank. Both institutions aim to use low-cost federal financing to spark investment across the country. Both institutions will also:

- Be financially self-sustaining. The European Investment Bank, which some observers have compared to a potential National Infrastructure Bank, had no negative budgetary impact in 2015. Based on our experience, we expect a National Green Bank to have a net zero budgetary impact, like other federal credit programs.

- Offer a range of financing tools to be responsive to local needs. Example tools include loans and loan guarantees.

- Leverage other funds from local governments and/or private investors. The Clinton campaign estimates that a $25 billion infrastructure bank would catalyze an additional $225 billion in infrastructure investment. A ratio of private to public investment of roughly 10:1 is similar to the impact we’ve seen Green Banks have on private investment in states like Connecticut.

- Choose recipients based on merit

Clean energy is different than other types of infrastructure

There are also several key differences between the National Infrastructure Bank and Green Bank. These differences reflect the fact that clean energy investments have different characteristics than other infrastructure investments. Clean energy projects like energy efficiency and solar can literally pay for themselves. By that, we mean the cash flows from clean energy projects are enough to pay for any financing, construction, and operating costs. While some toll roads are able to cover their costs, other road and infrastructure projects frequently do not generate enough cash flow to do this, relying on subsidies instead.

The attractive investment characteristics of clean energy is one of the reasons for the existence of a large and growing number of state and local Green Banks that invest in clean energy projects. Connecticut created the first state Green Bank in 2011. According to its most recent numbers, the Connecticut Green Bank has leveraged $181 million of its own funds to attract over $756 million of private investment in clean energy, for a total investment of $937 million. These investments supported the deployment of 194 MW of clean energy while creating over 11,700 job-years. Four other states have replicated Connecticut’s model by creating their own Green Banks. Montgomery County, Maryland recently became the first county to establish a local Green Bank. In our work around the country, we’ve heard from dozens of states, counties, and cities that are interested in building on this successful model—especially if federal financing becomes available.

The National Green Bank funds local institutions, not individual projects

The strength of state and local Green Banks means there are a number of existing and emerging institutions that can be financed. The National Green Bank is designed to directly finance these institutions, rather than projects. Financing institutions offers a number of benefits:

- Enable federal financing to support smaller scale projects. Small projects are often unable to access federal funds, yet small projects can be some of the most impactful clean energy projects. A residential energy efficiency loan, such as the Connecticut Green Bank’s Smart-E program, is frequently less than $10,000. The ability to reach smaller project sizes is especially critical to catalyzing growth in underserved markets, such as renters or low-income households.

- Support clean energy market development activities. Green Banks engage in activities that animate demand and resources for clean energy by providing education, outreach, and other types of support. This work fills a critical gap in a still-developing market, allowing clean energy financing vehicles to emerge and flourish.

- Give control over investment to local institutions with deep knowledge of local energy markets. Energy markets and needs vary dramatically from state to state. Green Banks are well positioned to under their unique markets and make decisions about which markets to enter and projects to finance. This means more effective investing.

In contrast, a National Infrastructure Bank would be designed to provide low-cost financing to large-scale projects of “regional or national significance.” Project examples could include highways, broadband networks, and water systems. These projects are typically enormous; a previous proposal set the minimum project size for a National Infrastructure Bank at $100 million. While over the last 25 years State Infrastructure Banks have been established, they have been wildly unevenly used and are not a significant part of plans for a National Infrastructure Bank. Large-scale infrastructure projects often hinge on the cost of financing, and are less in need of the market development work provided by local institutions.

Room for both

Catalyzing growth in clean energy and infrastructure overall are both important goals. The best approach is to have two national institutions that are self-sustaining and address the specific barriers in each market.

By Coalition for Green Capital

- Rapidly accelerate solar adoption in order to displace fossil fuel-based electricity;

- Ensure that solar is cheaper than grid power, so customers save money; and

- Do so at the least possible cost to taxpayers.

Green Banks are aligned with these objectives. Achieving these goals requires enabling market growth with financing, and reducing the amount of subsidy available as less is required. Subsidies have played a critical role in driving clean energy markets, because they change the economic calculus for customers by lowering the effective price of solar electricity so that it is competitive with the grid. Financing is crucial because it eliminates upfront cost to customers, so that they can enjoy cheaper electricity, paid off over time.

As the cost of solar technology falls, though, the level of subsidy needed to make solar price competitive with the grid should also fall. Lowering subsidies in a vacuum, without offering other forms of market support to ensure customers can still cover the upfront cost, may slow market growth. But if subsidies are lowered predictably and supplemented with increased financing, then solar adoption can continue at lower cost to the public.

This is where Green Banks come in. Green Banks can ensure that affordable financing is available to cover 100% of the upfront cost of solar. As access to financing increases, and as installation costs continue to fall, governments can step down subsidy levels.

The net result is continued solar market growth, but with lower net public cost. Public sector cost is reduced because public capital offered in the form of financing is repaid, which is different from a subsidy (an expense that is not repaid). Customers can adopt solar with no money out of pocket, enjoy solar electricity that is cheaper than grid power, and the total cost to taxpayers is lowered.

This transition from subsidies to finance is already taking place in Connecticut, with tremendous success. The Connecticut Green Bank, in addition to supporting finance for solar, is also tasked with managing the state’s residential solar subsidy program, known as RSIP. The Connecticut Green Bank has prudently managed the wind down of the program, lowering the subsidy per watt based on market conditions and feedback from installers.

At the same time, the Connecticut Green Bank has ensured multiple financing products are available for homeowners. And they’ve worked closely with installers to educate them on the finance products, provide marketing collateral and explain the enormous business opportunity available. As a result, installers have a powerful tool to sell their product, and have a clear understanding of why and when subsidies are falling. Installers are hugely supportive of this approach, and the market is steadily growing with lower subsidies.

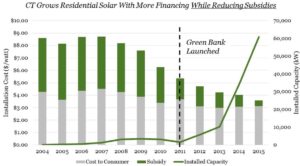

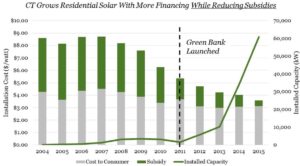

The chart below tells the story clearly. Residential rooftop solar adoption is skyrocketing in Connecticut. And at the same time, the level of subsidy offered to customers has fallen precipitously.

There are two key takeaways from this chart:

- The Connecticut residential solar market was weak, despite enormous subsidies, prior to the creation of the Green Bank. Once the Green Bank was created, solar adoption took off. And not all of this growth was financed by the Green Bank. Private sector finance companies, like SolarCity, only came to the Connecticut market after the Green Bank was created. This is despite the fact that the Green Bank offered financing to local installers, which looked like a competing product. For private financiers, the Connecticut Green Bank was a signal to the market that the state was focused on sustainable and rapid market growth.

- Though the cost of installing solar fell significantly over this period, the actual net cost of solar to the customer remained relatively flat (as shown by the grey bars). This is because the benefit of reduced installation cost mostly accrued to the government, as it lowered the subsidy level. So the net cost to customers for solar was effectively the same in 2015 as it was in 2011. However, annual deployment increased from zero to 60 MW. This is because financing solutions are now plentiful, allowing solar adoption with zero upfront cost. By eliminating the barrier of upfront cost, despite lower subsidies, rooftop solar became far more accessible and attractive.

All states can replicate this approach of ramping down subsidies as costs fall and increasing financing through and with Green Banks. The timing of this transition will vary across markets, as keeping solar power competitive with the grid depends on local electricity prices. But there are states today that offer rich subsidies for solar that are completely unnecessary—where solar adopters are able to enjoy solar power at prices far below grid price. Customers don’t need this level of subsidy, and there is no need for taxpayers to bear the cost. These states should shift that funding from subsidies to financing as Connecticut has, enabling market growth at lower taxpayer cost.

CGC’s Resources Page: Full of Excellent Content

By Coalition for Green Capital

Here are quick examples of the content we’ve posted on our Resources Page:

- CGC’s new Green Bank Resources Page includes the Nevada Green Bank Report and related presentations that CGC recently completed for the Nevada state legislature. This work was done in partnership with the Governor’s Office of Energy, and outlines specific market opportunities and implementation plans for the creation of a Green Bank in great detail.

- CGC has also posted a thorough report it completed for the Maryland legislature. The report goes into great detail on the necessary steps that must be taken to transform the Maryland Clean Energy Center, an existing clean energy financing institution, into a full-fledged Green Bank. The report includes specific analysis of the markets a Green Bank could serve, what financial products would be most effective in Maryland, and how to capitalize a Maryland Green Bank.

- CGC’s Green Bank White Paper, which details the key features and activities of a Green Bank, as well as pathways for creating Green Banks, is also available on the Resources Page. This is an excellent resource for anyone seeking a comprehensive introduction to the core Green Bank concept.

And there is a great deal of quality content on the Resources Page beyond these three examples! We encourage visitors to explore and learn from the content on our Resources Page. We’ll be constantly adding to the page with more original content, and linking to valuable materials from operating Green Banks around the world.

RI Infrastructure Bank Launches C-PACE

By Coalition for Green Capital

Rhode Island Follows Connecticut’s Footsteps

The Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank (RIIB) has officially launched the state’s C-PACE program. RIIB, Rhode Island’s Green Bank, has followed the Connecticut Green Bank’s successful model of using a centralized statewide PACE administrator.

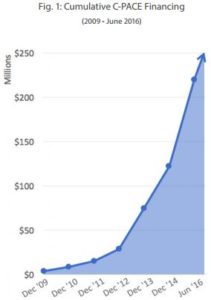

The numbers prove the success of the centralized commercial PACE administration model. Connecticut’s C-PACE program has closed $115 million in transactions through Q1 2016, accounting for nearly half of the entire national commercial PACE market. CT’s model has achieved this success despite Connecticut having only 1% of the national population.

Key Benefits of Statewide PACE Administrator

In following this single statewide PACE administrator model, Rhode Island will enjoy two key benefits:

- Consistency across the state

- Local governments avoid the burden of PACE administration

A single statewide administrator plays a very important role in facilitating consistency across many aspects of a PACE program. An administrator can promote consistency in program rules, underwriting criteria, project eligibility, consumer protection standards, collections and accounting systems, application processes, forms and documentation. This kind of standardization is vital for transforming the PACE market—consistency across projects and geographies reduces transaction costs and makes investments more attractive to private investors. The result is more private capital flows into the state’s PACE market.

A single statewide administrator can also help ensure the success of the PACE program by relieving local governments of the various burdens associated with administering a PACE program. Statewide PACE administrators can interface with local governments, help them set up collection and accounting systems for the PACE financing, and serve as a central point of contact and information for capital providers, contractors, and property owners that want to participate in the PACE program.

In following the statewide PACE administration model that was pioneered in Connecticut, RIIB has engineered its PACE program for success.

Rhode Island C-PACE Picking Up Steam

Rhode Island’s C-PACE program allows owners of eligible commercial and industrial buildings to finance up to 100% of energy efficiency, renewable energy and water conservation improvements, and repay those loans on property tax bills.

RIIB has contracted with Sustainable Real Estate Solutions to administer the program. The C-PACE program has an open capital platform, meaning any lender can participate and make loans through RIIB’s C-PACE structure. Long-term financing through RIIB’s C-PACE will enable building owners to make deep, multi-measure retrofits with long payback periods, where the term of financing matches the life of the measure (up to 25 years).

Out of the state’s 39 municipalities, seven municipalities are already participating in this statewide program, and seven more are discussing participation.

By Coalition for Green Capital

Yesterday, the nation’s first local Green Bank, the Montgomery County Green Bank, was designated as the County’s official Green Bank by the Montgomery County (MD) Council. The Montgomery County Green Bank will allow residents and businesses in Montgomery County to access low-cost financing for clean energy and energy efficiency projects.

In response to the official designation of the Montgomery County Green Bank as the County’s Green Bank, Coalition for Green Capital CEO Reed Hundt said, “We are grateful for the leadership of Councilmember Roger Berliner, Council President Nancy Floreen, and County Executive Ike Leggett as Montgomery County creates the nation’s first local Green Bank, the Montgomery County Green Bank. The Montgomery County Green Bank will offer an example for cities and counties across the United States as a way to invigorate local economies with investments in clean energy and energy efficiency technologies.”

Michelle Vigen, Senior Energy Planner at the Montgomery County Department of Environmental Protection, said, “We are pleased to be working with the Coalition for Green Capital to build out the Montgomery County Green Bank as a model for driving investment in local economies. Montgomery County has taken a leadership position in building out a clean energy economy in Maryland, and the nation’s first local Green Bank is a major element of our strategy of achieving our aggressive clean energy goals.”

Last summer, Councilmember Roger Berliner led the charge to pass legislation authorizing the Montgomery County Green Bank. Since the passage of Bill 18-15, the Coalition for Green Capital has worked hand-in-hand with Montgomery County staff to run a working group process to identify opportunities for the Montgomery County Green Bank, perform extensive market research and stakeholder interviews, incorporate the organization within the State of Maryland, and select a Board of Directors for the organization.

The Coalition for Green Capital will continue to work with Montgomery County as it builds the organization and begins to increase investment in the county’s clean energy and energy efficiency industries. The Coalition for Green Capital is a national nonprofit with a mission of accelerating the transition to the clean energy economy by establishing Green Banks at the local, state, federal, and international level.

By Reed Hundt

EVs, CAFE Standards, Gas Tax, Public Transportation

The right goal for reducing the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the transportation sector can be explained in a formula:

(GHGs/Gas-Powered Mile) x Total Gas-Powered Miles = Total GHG.

There are three ways to reduce total GHG in the transportation sector:

- CAFE Standards increase the gas-powered miles that come from each gallon of gas, while the GHGs from each gallon of gas stay constant. As an example, if CAFE produces a 10% gain in fuel efficiency and if total gas-powered miles driven stays constant, then GHGs drop by 10%.

- People to telecommute or take public transit, perhaps as a result of gas taxes or attractive public transportation options. Gas-powered miles go down, so GHGs go down (even if the ratio of GHGs to gas-powered mile stays constant).

- Electric vehicles replace gas-powered vehicles, which reduces gas-powered miles go down. Similarly more hybrid vehicles, which replace a portion of gas-powered miles driven with electric miles driven, would also reduce the gas-powered miles driven.

The formula demonstrates that it is possible, and desirable, to determine the equilibrium between a gas tax and a subsidy for EVs. As an example, if a state gas tax collecting $10 million reduced GHG by the same amount as a $10 million subsidy for EVs (or electric miles driven by a hybrid), then the only difference is who pays. In the case of the gas tax, it is the driver. In the case of the EV subsidy, it is the taxpayer. The gas tax is probably regressive; the EV subsidy, progressive.

The Three Best EV Subsidy Options

The next question is how to maximize the reduction in gas-powered miles that an EV subsidy could produce. The goal is captured in the following formula:

Gas-Powered Miles Reduction/$ = GHG reduction.

So what are the ways that an EV subsidy can lead optimally to gas-powered miles reduced? At least the following methods are possible:

- Award the subsidy per electric mile driven, on the assumption that any such mile driven in an EV substitutes for a gas-powered mile.

- Award the subsidy to vehicles according to the likely number of miles they will drive. For example, a taxi cab will be driven 70,000 miles a year in New York City, whereas the normal passenger car is used 10,000 miles a year. Cars used primarily for ride-hailing services (like Uber and Lyft) are similarly high mileage compared with an average passenger vehicle. Of course the vehicles with high annual usage are better targets for subsidies, as they displace more gasoline use.

- Award the subsidy by auction, picking the winner according to who shows the biggest number of electric miles substituting for gas-powered miles.

A few tweaks in EV subsidy policy can have large effects on emissions in the transportation sector. The current policy of giving the same subsidy to an EV that mostly sits in a garage to an EV that is driven over 70,000 miles per year doesn’t make much sense. The expense to the taxpayer is the same, but the miles (and associated GHGs offset) are very different. If we want EVs to contribute to lower GHG emissions, we would do better to target subsidies to cars that have high annual mileage.

Financing EV Charging Stations Through Auctions

As to charging stations, unfortunately every charging station installed anywhere today creates direct negative net present value. (There may be indirect benefits, such as more time spent in a retail store, or increased employee loyalty.) Charging stations are complementary products to EVs. They are like shoestrings for shoes—necessary but not valuable in and of themselves. They impose a cost that has to be paid by someone; they are not, in today’s market, a productive investment.

The goal of any economic policy is to reduce costs for the same output, or to reduce the ratio of cost to output. That is tantamount to saying that the goal of policy is to increase productivity. Everyone agrees that national income will not go up over the long run unless productivity goes up.

Therefore the goal as to charging stations is to make sure the smallest possible number are installed that nevertheless suffices to make EVs useful. (One might argue that charging station grids should compete to reduce costs, but where every such grid is net present value negative then the first will be a natural monopoly. Who would enter the market in order merely to lose less money than the first stations installer?) As a result, the right policy is for the subsidy provider to design the minimal station network necessary to make EVs useful. No one needs two pairs of shoestrings for the same shoes; no one needs more than the minimum necessary charging stations.

Whether the subsidy provider is the government, the utility, or the EV industry, in any case the provider should design the optimal network and award a license to build it by means of an auction that selects the lowest cost provider as the winner of the necessary subsidy.

Follow

The Clean Energy Future Blog

for links, analysis, and commentary on the world of green banks and clean energy investment