The goal of any government’s solar policy should be to:

- Rapidly accelerate solar adoption in order to displace fossil fuel-based electricity;

- Ensure that solar is cheaper than grid power, so customers save money; and

- Do so at the least possible cost to taxpayers.

Green Banks are aligned with these objectives. Achieving these goals requires enabling market growth with financing, and reducing the amount of subsidy available as less is required. Subsidies have played a critical role in driving clean energy markets, because they change the economic calculus for customers by lowering the effective price of solar electricity so that it is competitive with the grid. Financing is crucial because it eliminates upfront cost to customers, so that they can enjoy cheaper electricity, paid off over time.

As the cost of solar technology falls, though, the level of subsidy needed to make solar price competitive with the grid should also fall. Lowering subsidies in a vacuum, without offering other forms of market support to ensure customers can still cover the upfront cost, may slow market growth. But if subsidies are lowered predictably and supplemented with increased financing, then solar adoption can continue at lower cost to the public.

This is where Green Banks come in. Green Banks can ensure that affordable financing is available to cover 100% of the upfront cost of solar. As access to financing increases, and as installation costs continue to fall, governments can step down subsidy levels.

The net result is continued solar market growth, but with lower net public cost. Public sector cost is reduced because public capital offered in the form of financing is repaid, which is different from a subsidy (an expense that is not repaid). Customers can adopt solar with no money out of pocket, enjoy solar electricity that is cheaper than grid power, and the total cost to taxpayers is lowered.

This transition from subsidies to finance is already taking place in Connecticut, with tremendous success. The Connecticut Green Bank, in addition to supporting finance for solar, is also tasked with managing the state’s residential solar subsidy program, known as RSIP. The Connecticut Green Bank has prudently managed the wind down of the program, lowering the subsidy per watt based on market conditions and feedback from installers.

At the same time, the Connecticut Green Bank has ensured multiple financing products are available for homeowners. And they’ve worked closely with installers to educate them on the finance products, provide marketing collateral and explain the enormous business opportunity available. As a result, installers have a powerful tool to sell their product, and have a clear understanding of why and when subsidies are falling. Installers are hugely supportive of this approach, and the market is steadily growing with lower subsidies.

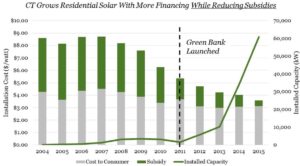

The chart below tells the story clearly. Residential rooftop solar adoption is skyrocketing in Connecticut. And at the same time, the level of subsidy offered to customers has fallen precipitously.

There are two key takeaways from this chart:

- The Connecticut residential solar market was weak, despite enormous subsidies, prior to the creation of the Green Bank. Once the Green Bank was created, solar adoption took off. And not all of this growth was financed by the Green Bank. Private sector finance companies, like SolarCity, only came to the Connecticut market after the Green Bank was created. This is despite the fact that the Green Bank offered financing to local installers, which looked like a competing product. For private financiers, the Connecticut Green Bank was a signal to the market that the state was focused on sustainable and rapid market growth.

- Though the cost of installing solar fell significantly over this period, the actual net cost of solar to the customer remained relatively flat (as shown by the grey bars). This is because the benefit of reduced installation cost mostly accrued to the government, as it lowered the subsidy level. So the net cost to customers for solar was effectively the same in 2015 as it was in 2011. However, annual deployment increased from zero to 60 MW. This is because financing solutions are now plentiful, allowing solar adoption with zero upfront cost. By eliminating the barrier of upfront cost, despite lower subsidies, rooftop solar became far more accessible and attractive.

All states can replicate this approach of ramping down subsidies as costs fall and increasing financing through and with Green Banks. The timing of this transition will vary across markets, as keeping solar power competitive with the grid depends on local electricity prices. But there are states today that offer rich subsidies for solar that are completely unnecessary—where solar adopters are able to enjoy solar power at prices far below grid price. Customers don’t need this level of subsidy, and there is no need for taxpayers to bear the cost. These states should shift that funding from subsidies to financing as Connecticut has, enabling market growth at lower taxpayer cost.