The Clean Energy Future Blog

By Catherine Beck

A recent story by Jackie Toth in Morning Consult explores ways that Green Banks could benefit from proposed modifications to a loan guarantee program currently available through the Department of Energy. A bill, reintroduced by Sen. Lisa Murkowski, would specify that “state-based lenders” (which would include Green Banks) would have access to the loan guarantee program.

The story quotes CGC Executive Director Jeff Schub:

It is increasingly common to create green banks as nonprofits that are still connected to state governments, said Jeff Schub, executive director of the Coalition for Green Capital. Murkowski’s bill would also allow the participation of groups like Michigan Saves, which is a nonprofit green bank initially created by a state grant.

The bill would also exempt state financing entities from a requirement that an eligible project use “new or innovative” technology. This could help to streamline a review process that could otherwise last weeks or months, and give a wider range of project types access to the program.

For more details, see the full story from Morning Consult here.

For more on the accomplishments of state and local Green Banks in the US, see the Annual Industry Report of the American Green Bank Consortium.

By Coalition for Green Capital

This post originally appeared on the site of CGC’s campaign for a federal Green Bank.

Results from a new poll of eligible voters has found that a majority of all voters support the National Climate Bank, including majorities of Democrats and Independents, as well as a plurality of Republicans.

The poll also found that voters would be more likely to support a candidate that supports the National Climate Bank, with 45% of all voters and 64% of Democrats saying that their support would increase.

Some takeaways:

- Support/oppose for the National Climate Bank is +43 among all voters, +70 among Democrats, +42 among Independents, and +10 among Republicans.

- Large majorities of Democrats support buying coal to keep it in the ground (66%), and paying coal and gas plants to close (68%).

- Democrats are more likely to vote for a candidate who supports the Climate Bank versus one who does not, by 64% to 7%.

These results are especially relevant as Democrats prepare for CNN’s town hall on climate, taking place Sept. 4.

For more details, see the full results.

By Coalition for Green Capital

This post originally appeared on the site of CGC’s campaign for a federal Green Bank.

This week’s story by Joe Gose in the NYT provides an excellent overview of Commercial Property Assessed Clean Energy (C-PACE) programs, bringing this “little-known” way to secure low-cost capital into view for a wider audience.

The piece describes the features that make C-PACE financing so attractive for clean and energy-efficient development. A conventional loan is taken out and paid back by an individual person or business, but a loan through a C-PACE program is attached to a property and paid as part of the real estate tax bill.

C-PACE gives borrowers more freedom to take on long-term loans and make significant improvements to their buildings. Under a conventional loan agreement, borrowers may worry about what will happen if they need to sell the building before the loan is repaid. The bank making the loan also has to be concerned about the risk that the borrower may default. These concerns can lead borrowers to take out shorter loans for smaller amounts, and banks to charge high rates for the loan.

But, in many cases a larger investment could greatly improve a building’s value and lower its monthly energy bills. With C-PACE, the loan transfers to the new buyer if the building is sold, reducing costs and risks for both the lender and the borrower. As the NYT quotes from one developer:

“Developers are always on the lookout for new tools to make their projects better,” said Michael T. Moylan, president of Shamrock Development. “We saw that PACE was going to be good for us — it made our buildings more energy efficient, and long-term fixed-rate financing is always attractive.”

While the NYT mainly looks ahead to the future of PACE, the program’s history is tied closely to Green Banks. The Connecticut Green Bank played a key role in the expansion of C-PACE in 2012. The model spread, and C-PACE is now offered through other Green Banks including in NYC and Rhode Island.

As CGC Executive Director Jeff Schub described to Yale Insights in a recent interview, the Connecticut Green Bank was instrumental in helping C-Pace to gain traction:

Initially, when the Connecticut Green Bank launched the program, private lenders weren’t actually making any loans, so the green bank used its own funds to finance C-PACE projects. Then they securitized those loans and sold them into a secondary market.

Very quickly, that scaled C-PACE to a very different level. The Connecticut Green Bank partnered with a private financial institution, Hannon Armstrong, to set up a $100 million warehouse to co-invest in C-PACE projects. Many more private lenders have come into the market and are making loans and sales all the time.

Looking ahead to the future, another factor not mentioned in the story could be important to C-PACE: the National Climate Bank. With $35 billion to invest and capitalize state and local Green Banks, the Climate Bank could help these successful programs expand still further, saving both energy and money for businesses across the country.

With long-term energy storage becoming more important to the grid, new technologies compete for investment

By Coalition for Green Capital

This post originally appeared on the site of CGC’s campaign for a federal Green Bank.

Recent weeks have included a drumbeat of news about long-term energy storage, as start-up companies seek funding for very different approaches. A few examples via Greentech Media:

- Closed-loop pumped hydro storage. Two artificial reservoirs, one higher and one lower, that can pump water to the higher reservoir to store energy and drain into the lower reservoir to release energy.

- Electrochemical batteries. The most commonly-used lithium-ion batteries can store large amounts of power for a few hours, but new chemical formulas are stretching that time to last days or longer.

- Gravity storage. A tower of concrete blocks, with a six-armed crane at the center that raises the blocks to store energy and lowers them to release energy.

As renewable energy becomes a larger part of our energy mix, the ability to store large amounts of energy for longer periods of time will become more important. Solar and wind provide fluctuating amounts of power, the timing of which doesn’t always correspond to the time of greatest customer demand. Energy storage allows that power to be saved for when it’s needed most.

This in turn can reduce the need for fossil-fueled peaking plants to come online at times of high demand, improve the stability and reliability of the grid, save money, and reduce emissions.

But despite their importance for the future of the clean energy transition, storage technologies like the examples given here have faced a variety of obstacles. Federal research and development programs, along with venture capital, are critical players at the earliest stages. Still bigger gaps exist in bringing these technologies to commercial scale, and Green Banks have begun to focus on removing financial barriers to the widespread adoption of storage.

In the first annual report of the American Green Bank Consortium, energy storage was highlighted as a trend in 2018. The New York Green Bank and the Nevada Clean Energy Fund both took steps to promote investment in energy storage and dialogue with storage developers. The National Climate Bank Act also explicitly mentions energy storage as an qualified technology, and would be able to mobilize far greater amounts of private investment into developing new energy storage resources.

The deployment of energy storage is critically important to the future of the grid, and Green Banks have a key role to play in making it happen.

By Coalition for Green Capital

With the National Climate Bank Act introduced in the Senate, interest is growing in how Green Banks can fight climate change and finance the clean energy transition. Yale Insights interviewed CGC’s Executive Director Jeff Schub where he explained how and why Green Banks can have such a great impact:

Hundreds, if not thousands, of very large financial institutions—often backed by governments—are financing fossil fuels. If we’re going to counteract that, we need a climate-focused, mission-driven financial institution.

The discussion touches on why the private sector needs help in order to transition the energy sector at the speed required to avoid the worst impacts of climate change, and how existing Green Banks have already demonstrated successful methods to do so.

The conversation also emphasized the social and environmental justice concerns which existing Green Banks are already working on, and which the National Climate Bank would be empowered to prioritize. Low-income households already devote a greater portion of their income to energy, so it’s especially necessary to take their needs into account.

Read the full piece at Yale Insights.

By Coalition for Green Capital

This post originally appeared on the site of CGC’s campaign for a federal Green Bank.

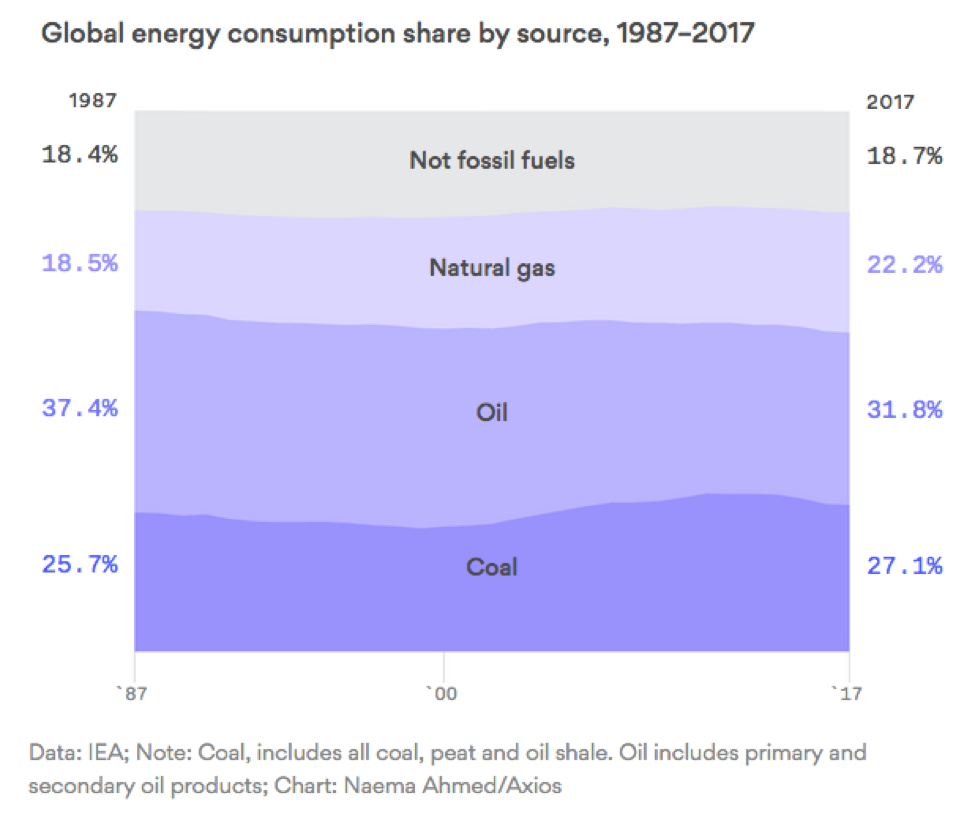

In today’s column, Amy Harder at Axios highlights “the most important boring chart out there.” Here it is:

The chart is “boring” in that it’s almost completely static, showing little change in the global energy mix over the course of three decades. And it’s important in that it shows the magnitude of the challenge ahead to avoid the harmful consequences of climate change. Until these numbers change, the climate crisis will continue to worsen.

How can this be, when it seems that we’re constantly reading about advances in renewable energy? The buildout of renewable energy for power generation has accelerated, but so has the demand for power. Energy use for transportation and industry has also increased, without becoming cleaner at the same rate that the power sector has. Some countries, primarily developed countries, have slightly reduced their emissions, while emerging economies have increased their emissions.

Despite major changes in specific sectors and regions, we end up with a total global picture that’s remarkably stable. As the column states:

“Renewable electricity (which is the primary use for wind and solar) is often being added on top of instead of in lieu of fossil fuels, particularly in Asia’s rapidly growing economies.”

This high-level view provides a sobering chaser to positive indicators like lasts week’s move by Moody’s to downgrade the ratings of North American coal, and shows why ambitious policies like a National Climate Bank must focus on replacing fossil-fuel energy use (rather than just meeting new demand) in order to move these numbers away from stasis.

For more, read Amy Harder’s full insightful column in Axios here.

Follow

The Clean Energy Future Blog

for links, analysis, and commentary on the world of green banks and clean energy investment